- Home

- Jennifer Ashley

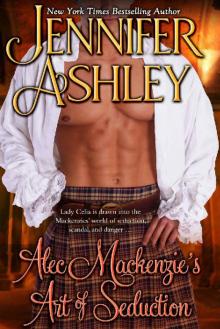

Alec Mackenzie's Art of Seduction

Alec Mackenzie's Art of Seduction Read online

Alec Mackenzie's Art of Seduction

Mackenzies, Book 9

Jennifer Ashley

JA / AG Publishing

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Epilogue

Mackenzie Family Tree

Excerpt: Death Below Stairs

Also by Jennifer Ashley

About the Author

Copyright

Chapter 1

The Attic of Kilmorgan Castle, June 1892

Ian Mackenzie heard his name like music on the air. He didn’t look away from the task he’d set himself, laying each page in its neat stack on the desk, exactly where it needed to go. He knew Beth would come to him the same as he knew when his next breath would be.

She entered the attic with a rustle of skirts, pausing in the open doorway to push a strand of hair from her face. Ian did not have to glance up at her to follow her every move.

“Ian? What on earth are you doing?”

Ian did not reply until he’d laid another page in its stack and squared it to match the notebook next to it. Beth liked him to answer, but Ian wanted to think out the sentences in his head beforehand so he could respond to her satisfaction. What he considered the most important part of an explanation was not always what others did.

“Reading,” he said after a moment. “About the family.”

“Oh?” Beth moved to him, the faint cinnamon scent that clung to her distracting. “You mean your family history?”

Ian had divided the surface of the large kneehole desk, left over from a century ago, into sections, one for every generation of the Mackenzie family. Those sections were divided into immediate members of that family. Papers, letters, ledgers, and notebooks had their own piles in each section, and they were stacked chronologically.

He laid his broad hand on the leftmost pile. “Old Malcolm.” Malcolm’s wife Mary’s journal had provided entertainment for many a winter night with tales of Malcolm’s exploits.

“Alec Mackenzie.” Ian rested his hand on the next pile then the one after that. “And Will.”

“You found their papers?” Beth asked in surprise. “I thought Alec and Will Mackenzie fled into exile after Culloden, when the entire family was listed as dead.”

Ian shrugged. “All is here.” He didn’t speculate on how the letters and journals of Will, Alec, and their families had arrived at Kilmorgan—he only cared that they had.

“Have you read them?” Beth looked over the neat stacks, a little smile on her lips. Ian had come to learn this expression meant she was interested.

Ian didn’t answer. He’d of course read each paper, each notebook, before deciding into which stack it should go.

Alec Mackenzie had left sketchbooks full of drawings of his children, his wife, his brothers, his sisters-in-law, his father. Another portfolio held sketches of the skylines of London and of Paris, and of the lands around Kilmorgan, as well as portraits of Alec Mackenzie himself, some of them intimate, Alec only a kilt, a wicked glint in his eye.

Ian opened one of the sketchbooks and pushed it toward Beth. This was of Alec as a young man, dressed in the manner of the early eighteenth century. His pale shirt had cotton lace at the cuffs, his long hair was pulled into a queue, and a strong face laughed out of the picture at them.

“Intriguing.” Beth’s breath was warm on Ian’s cheek. “He was the artistic one, I gather, like Mac.” She touched the paper. “But who drew this? Was his wife an artist too?”

“Celia.” Ian turned over a page to show a young woman with dark curls under a small lacy cap, a round face, and a rather impish smile. “She drew the cities.”

“Oh.” Beth clasped her hands as Ian revealed a stretch of London as it had been in 1746. Rooftops marched through the fog—she recognized the view from Grosvenor Square toward Piccadilly and Green Park, but gaps existed where houses were now. “That must be the sketch for the painting that hangs in Mac’s wing. How exciting.” She looked at Ian with shining eyes. “Tell me about them.” Her smile widened. “I know you remember every word of these.” She touched the cover of a journal.

For a moment, Ian’s interest in his ancestors faded as he lost himself in Beth’s brown eyes. Beth was beauty, she was silence, she was the peace in his heart.

She was also stubborn in her own quiet way. She grasped his sleeve and towed him to a dusty settee, one gilded and upholstered in petit point, which had come to Kilmorgan straight from Versailles.

Beth nestled into Ian’s side and drew her feet up under her, a further distraction from deeds of the remote past. “Go on,” she said. “Tell me their story. All the details. I’ll let you know which bits to leave out when you tell it again to the children.”

Ian pictured the two of them gathering with Jamie, Belle, and Megan in one of their cozy chambers in Ian’s wing of the house, plus his son’s and daughters’ antics and blurted questions as Ian tried to tell them a straightforward tale. Jamie and Belle especially constantly interrupted him, and stories rarely got finished the way Ian planned them. He looked forward to it.

For now, Beth was warm at his side, her hair soft beneath his lips.

“Once upon a time,” he began—Beth had explained that all stories should begin with Once upon a time.

“A few months after the Battle of Culloden,” Ian continued, “Alec Mackenzie left Paris and returned to England, in search of Will, who’d vanished for too long a while. Will’s contacts hadn’t seen him, rumor had it he might have been arrested, and the family was worried.

“The last place Will had been reported was London, so Alec packed his things, took his daughter, assumed a false name, and went to London …”

London, 1746

The screaming wove through Alec Mackenzie’s dreams and jerked him from sleep.

For a breath he was back on the battlefield, men keening as they died. Soldiers shoved swords into his clansmen, his friends—never mind they were injured and begging for mercy.

Another breath, and the noise resolved itself into the wail of a child who didn’t understand the pain of new teeth.

Alec wrenched himself out of bed, his nightshirt slipping from one large shoulder, his dark red hair tumbling into his eyes. He righted the nightshirt and stumbled into the chilly hall, not worried about trivial things like dressing gown and slippers.

No one stirred in the upper floors of the dark house on Grosvenor Square. This was one of the square’s larger mansions, six stories high, four rooms wide, and several rooms deep. Alec’s chamber was one floor down from the attic, his hostess pretending that Alec’s position wasn’t quite that of a servant.

Alec’s daughter, Jenny, on the other hand, had to keep to a room in the attics, lest his hostess’ guests, the cream of London’s intellectual society and patrons of the arts, discover that a child actually stayed in the house.

One-year-old Jenny didn’t care where she slept, but the positioning of the rooms made it a job to rush to Jenny’s side when she needed her da’.

>

Alec shouldered his way to the back stairs and hurried up a flight. His feet, hardened from running over Highland hills, never felt the roughness of the wooden stairs.

He bolted into Jenny’s nursery, cursing when he didn’t see the nursemaid Lady Flora had hired. The poor woman needed to sleep, of course, but she was snoring in the next room through Jenny’s screams, which were winding up to a pure Highlander howl. Alec’s youngest brother, Mal, had screeched like that.

“All right, wee one,” Alec whispered in Erse as he lifted his daughter into his arms, her soft warmth against his cheek. “Papa’s here.”

Jenny continued to cry, but she turned to Alec’s shoulder and snuggled down, recognizing her father. Alec held her close, snatching up the bottle of medicine the nursemaid had concocted for Jenny’s teething. Swore by it, the woman did.

Alec worked off the cork one-handed and flinched when the acrid stench of pure gin curled into his nose.

“Bloody hell.” Alec threw the bottle into the smoldering fire, where it splintered, sending a spurt of blue flame up the chimney. “Well, lass, we’ll have to find ye another nursemaid in the morning, won’t we? One who won’t poison ye with this filth.”

In the meantime, there was nothing to soothe Jenny’s pain, no other food, drink, or medicine near.

The room was cold as well. The small fire was here at Alec’s insistence—Lady Flora’s austere housekeeper saw no reason to waste fuel on a babe.

Alec lifted Jenny’s blankets from her cot, wrapped her up, and carried her down the stairs to his own bedchamber. He laid her in the bed and then folded his big frame into a chair that he dragged next to it, not wanting to take the chance of rolling on her in his sleep. She was so tiny, and Alec was a bloody great Highlander.

Jenny warmed and calmed, Alec’s big hand on her back, and she slept. Alec watched her, knowing that if anyone found Jenny here, he’d be standing before his hostess while she lifted her nose in the air and reminded him exactly how dangerous was his mission and that he should have left his child in France.

His daughter was silent now, sleeping in innocent happiness. Alec pulled a quilt over himself and drifted off, his slumber not quite so innocent and in no way happy.

But Jenny was safe, all that mattered for the moment. Now to make sure the rest of his family was as well.

“You’re late,” Lady Flora, Dowager Marchioness of Ellesmere, said as Lady Celia Fotheringhay hastened into Lady Flora’s private salon, Celia’s portfolio sliding dangerously from under her arm.

Celia had never been in this room before. Whenever she called upon Lady Flora, she was only allowed into the grand salon, which was two stories high, gilded and painted within an inch of its life, and stuffed with important people.

The right important people, Celia amended—the intellectuals and high-minded of the ton who supported the Whigs in their power and glory.

Celia had also never been inside this house without her mother, the formidable Duchess of Crenshaw. Lady Flora was said to eat innocent young ladies for breakfast, and so an older, stronger woman was a necessary guard.

For this visit, Celia was on her own and shown into a compact, sunny room on the first floor. This chamber was no less ostentatious than the grand salon, albeit on a smaller scale. The audience took place, alarmingly, at breakfast, and for an entirely different reason than Celia’s previous visits.

Lady Flora was forty but her slim body and unlined face compared to a woman of twenty. She wore her golden hair pulled back into a simple knot, and her light blue eyes held as much chill as her voice.

She looked up at Celia from the remains of a repast. Her empty plate was whisked away by a silent footman, while another equally silent footman placed a cup by her elbow. Lady Flora poured thick coffee into it, the trickle of liquid breaking the delicate hush.

Celia’s portfolio chose that moment to slip to the floor with a clatter. The clasp broke, and drawings of misty hills, vases of flowers, and Celia’s family cat floated across the carpet.

“Drat,” Celia said under her breath. The portfolio was awkward—she was always dropping the blasted thing.

To Lady Flora’s exasperated sigh, Celia fell to her knees, her striped skirts billowing, to collect the drawings. She heard Lady Flora sigh again, and the two footmen appeared next to Celia, collecting the pages with deft, gloved hands.

The footmen restored the drawings neatly and efficiently to the portfolio and laid the large thing at the end of the table. A maid appeared out of nowhere for the sole purpose of helping Celia to her feet, then vanished.

“You’re late,” Lady Flora repeated.

The gilded clock on the mantelpiece gently announced it was quarter past eight. “Mother was in a bit of a state this morning,” Celia said quickly as she brushed off her skirts. “There’s an important debate today, you see, and Papa was wavering on what he wanted to say …” Her mother’s opinion on his vacillation had rung through the house.

Celia trailed off under Lady Flora’s glare. Lady Flora obviously had no interest in the Duchess of Crenshaw’s machinations regarding Parliamentary debates, at least not at the moment.

“The drawing master I’ve engaged is celebrated the length and breadth of France,” Lady Flora said coolly. “He is instructing you as a favor to me, and to your mama.”

Celia knew good and well how obligated she was to her mother and Lady Flora. She’d been told so at least seventy-two times a day for the past several weeks, ever since the Disaster. Drawing lessons with a professional artist was only one idea about what to do with the problem of Celia.

Celia was still astonished that her mother had consented to let her have the lessons at all, but her father had for once squared his shoulders and taken Celia’s side against his wife. Then again, when Lady Flora explained that Celia could learn to paint portraits of the great and good of the Whig party, contributing to the cause of making Britain a world power, the duchess had capitulated.

Lady Flora’s glare strengthened as Celia stood mutely. The woman was quite beautiful, in a brittle sort of way, which made her more daunting. Celia knew she ought to pity Lady Flora, who’d been devastated when her grown daughter had died a few years ago, but any grief had long since frosted over.

“Well, go on up,” Lady Flora said impatiently. “A gaping mouth only lets in flies, so pray, keep it closed.”

Celia popped her mouth shut, made a polite curtsy, and said, “Yes, Lady Flora.”

As Celia turned to take up her portfolio, Lady Flora said witheringly, “No, no. A servant will carry it upstairs.”

Celia snatched her hands back from the portfolio and hastened to the door, eager to remove herself from Lady Flora’s presence. Before she could leave, however, she had to turn back.

“Um, where is the studio?”

Another heavy sigh. “Fourth floor, in the front, near the staircase. The footman will show you.”

Lady Flora waved a hand in dismissal—like the empress of a proud Oriental country, Celia reflected as she hurried away. She bit back a laugh picturing Lady Flora in flowing Chinese garments, flicking her fingers while hundreds of lackeys bowed to her on their knees.

Celia lost her smile quickly. The image was far too close to the mark.

She followed the footman in satin breeches and powdered wig out of the room and up three more flights of stairs. Celia was gasping by the time they reached the top, but the footman breathed as calmly as he would after a lazy stroll in a garden.

He opened a door and indicated, with an elegant gloved hand, that she should go inside. Celia scurried past him, and the footman bowed and withdrew, closing the door behind him, the latch catching with a faint click.

Celia found herself in a quiet room flooded with sunshine. The chamber held a few chairs and a recamier draped with red cloth, an easel, a table filled with jars and brushes, and another table strewn with square frames of wood, folds of canvas, and a sheaf of drawing paper.

A fire crackled in the heart

h, but except for Celia, the room was empty. No artist’s assistant bustled about preparing canvases or mixing paints, no artist looked up to comment on her tardiness.

Celia had met portrait painters, including the celebrated Mr. Hogarth, when they’d come to paint her mother, father, brother, and herself, and she knew what artists looked like. Her instructor would either be thin and nervous with a wife and five children to feed, or elderly, fussy, and set in his ways, with a habit of making inelegant noises.

Lady Flora had said the artist was celebrated in France, so Celia pictured a small, dark-haired man with a turned-up nose and a thick accent, who’d click his tongue against his teeth when he regarded Celia’s meager efforts.

Celia explored the room and the artist’s accoutrements as she waited, hoping to find an example of the drawing master’s work, but she saw none.

After a few moments, another footman discreetly glided in and laid Celia’s portfolio on a table then glided back out again.

Celia hastened after him to ask if he’d fetch the drawing master, but the footman had gone by the time she reached the hall. Lady Flora’s servants were trained to come and go like ghosts.

She hesitated in the stairwell, which was dim after the bright room, the only light coming from a shaded window on the landing.

How long was she to wait? Did the drawing master keep erratic hours, coming and going as he pleased? Was he a famous Frenchman quite annoyed he had to teach the likes of Lady Celia Fotheringhay, an English duke’s spoiled daughter? Had he drowned his frustration in wine and now snored away the morning?

Grant

Grant Pride Mates

Pride Mates The Duke's Perfect Wife

The Duke's Perfect Wife Scandal Above Stairs

Scandal Above Stairs White Tiger

White Tiger Midnight Wolf

Midnight Wolf Rules for a Proper Governess

Rules for a Proper Governess Wild Wolf

Wild Wolf Bad Wolf

Bad Wolf Lion Eyes

Lion Eyes Murder in Grosvenor Square

Murder in Grosvenor Square The Untamed MacKenzie

The Untamed MacKenzie Wicked Deeds of Daniel Mackenzie

Wicked Deeds of Daniel Mackenzie Tiger Striped_Shifters Unbound

Tiger Striped_Shifters Unbound Murder Most Historical

Murder Most Historical Shifter Made

Shifter Made Mate Bond

Mate Bond Tiger Striped

Tiger Striped Bodyguard

Bodyguard Guardian's Mate

Guardian's Mate From Jennifer Ashley, With Love

From Jennifer Ashley, With Love The Longest Night

The Longest Night The Stolen Mackenzie Bride

The Stolen Mackenzie Bride The Sudbury School Murders

The Sudbury School Murders The Care & Feeding of Pirates

The Care & Feeding of Pirates The Hanover Square Affair

The Hanover Square Affair Death Below Stairs

Death Below Stairs Wild Things

Wild Things Wild Cat

Wild Cat The Gentleman's Walking Stick

The Gentleman's Walking Stick A Regimental Murder

A Regimental Murder Lone Wolf

Lone Wolf Forbidden Taste

Forbidden Taste Red Wolf

Red Wolf The Madness of Lord Ian Mackenzie

The Madness of Lord Ian Mackenzie A Covent Garden Mystery

A Covent Garden Mystery The Pirate Next Door

The Pirate Next Door Past Crimes: A Compendium of Historical Mysteries

Past Crimes: A Compendium of Historical Mysteries Highlander Ever After

Highlander Ever After The Alexandria Affair

The Alexandria Affair A Shifter Christmas Carol

A Shifter Christmas Carol The Devilish Lord Will

The Devilish Lord Will Adam

Adam Kyle (Riding Hard Book 6)

Kyle (Riding Hard Book 6) A Body in Berkeley Square

A Body in Berkeley Square The Mad, Bad Duke

The Mad, Bad Duke Mate Claimed

Mate Claimed A Mackenzie Clan Christmas

A Mackenzie Clan Christmas The Seduction of Elliot McBride

The Seduction of Elliot McBride The Glass House

The Glass House Iron Master (Shifters Unbound Book 12)

Iron Master (Shifters Unbound Book 12) A Mackenzie Family Christmas: The Perfect Gift

A Mackenzie Family Christmas: The Perfect Gift Scandal Above Stairs_A Below Stairs Mystery

Scandal Above Stairs_A Below Stairs Mystery Perfect Mate

Perfect Mate Murder in the East End

Murder in the East End Snowbound in Starlight Bend

Snowbound in Starlight Bend Hard Mated

Hard Mated Murder in St. Giles

Murder in St. Giles Alec Mackenzie's Art of Seduction

Alec Mackenzie's Art of Seduction A MacKenzie Clan Gathering

A MacKenzie Clan Gathering Tyler

Tyler Lady Isabella's Scandalous Marriage

Lady Isabella's Scandalous Marriage Duke in Search of a Duchess: Sweet Regency Romance

Duke in Search of a Duchess: Sweet Regency Romance A Death in Norfolk

A Death in Norfolk Give Me One Night (McLaughlin Brothers Book 4)

Give Me One Night (McLaughlin Brothers Book 4) Iron Master

Iron Master The Many Sins of Lord Cameron

The Many Sins of Lord Cameron A Disappearance in Drury Lane

A Disappearance in Drury Lane Never Say Never (McLaughlin Brothers Book 3)

Never Say Never (McLaughlin Brothers Book 3) Death in Kew Gardens

Death in Kew Gardens Ross: Riding Hard, Book 5

Ross: Riding Hard, Book 5 Ray: Riding Hard

Ray: Riding Hard A Soupçon of Poison

A Soupçon of Poison Tiger Magic

Tiger Magic The Pirate Hunter's Lady

The Pirate Hunter's Lady A Mystery at Carlton House

A Mystery at Carlton House The Necklace Affair

The Necklace Affair Wolf Hunt

Wolf Hunt Scandal and the Duchess

Scandal and the Duchess Kyle

Kyle Why Don't You Stay? ... Forever (McLaughlin Brothers Book 2)

Why Don't You Stay? ... Forever (McLaughlin Brothers Book 2) Bear Attraction

Bear Attraction The Gathering

The Gathering A Mackenzie Yuletide

A Mackenzie Yuletide Wild Things (Shifters Unbound #7.75)

Wild Things (Shifters Unbound #7.75) The Redeeming

The Redeeming The Seduction of Elliot McBride hp-5

The Seduction of Elliot McBride hp-5 Death at the Crystal Palace

Death at the Crystal Palace Mackenzie Family Christmas: The Perfect Gift (highland pleasures)

Mackenzie Family Christmas: The Perfect Gift (highland pleasures) Forbidden Taste: A Vampire Romance (Immortals)

Forbidden Taste: A Vampire Romance (Immortals) Care and Feeding of Pirates

Care and Feeding of Pirates Shifter Made (shifters unbound)

Shifter Made (shifters unbound) Dark and Dangerous: Six-in-One Hot Paranormal Romances

Dark and Dangerous: Six-in-One Hot Paranormal Romances The Duke’s Perfect Wife hp-4

The Duke’s Perfect Wife hp-4 The Seduction of Elliot McBride (Mackenzies Series)

The Seduction of Elliot McBride (Mackenzies Series) Lady Isabella's Scandalous Marriage hp-2

Lady Isabella's Scandalous Marriage hp-2 BodyGuard (Butterscotch Martini Shots Book 2)

BodyGuard (Butterscotch Martini Shots Book 2) The Wicked Deeds of Daniel Mackenzie hp-6

The Wicked Deeds of Daniel Mackenzie hp-6 Tiger Magic su-5

Tiger Magic su-5 The Madness Of Lord Ian Mackenzie hp-1

The Madness Of Lord Ian Mackenzie hp-1 Alec Mackenzie's Art of Seduction: Mackenzies (Mackenzies Series Book 9)

Alec Mackenzie's Art of Seduction: Mackenzies (Mackenzies Series Book 9) Mackenzie Family Christmas: The Perfect Gift

Mackenzie Family Christmas: The Perfect Gift Bodyguard (Shifters Unbound #2.5)

Bodyguard (Shifters Unbound #2.5) Midnight Wolf (A Shifters Unbound Novel)

Midnight Wolf (A Shifters Unbound Novel) White Tiger (A Shifter's Unbound Novel)

White Tiger (A Shifter's Unbound Novel) Cowboys Last All Night

Cowboys Last All Night Pride Mates su-1

Pride Mates su-1 Hard Mated (shifters unbound )

Hard Mated (shifters unbound ) Bodyguard (shifters unbound )

Bodyguard (shifters unbound ) Snowbound in Starlight Bend: A Riding Hard Novella

Snowbound in Starlight Bend: A Riding Hard Novella The Untamed Mackenzie (highland pleasures)

The Untamed Mackenzie (highland pleasures) The Untamed Mackenzie (Mackenzies Series)

The Untamed Mackenzie (Mackenzies Series)![Highland Pleasures [6] The Wicked Deeds of Daniel Mackenzie Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/07/highland_pleasures_6_the_wicked_deeds_of_daniel_mackenzie_preview.jpg) Highland Pleasures [6] The Wicked Deeds of Daniel Mackenzie

Highland Pleasures [6] The Wicked Deeds of Daniel Mackenzie Lone Wolf (shifters unbound)

Lone Wolf (shifters unbound)![Shifters Unbound [5] Tiger Magic Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/11/shifters_unbound_5_tiger_magic_preview.jpg) Shifters Unbound [5] Tiger Magic

Shifters Unbound [5] Tiger Magic Tyler (Riding Hard Book 4)

Tyler (Riding Hard Book 4) Ross

Ross Bad Boys of the Night: Eight Sizzling Paranormal Romances: Paranormal Romance Boxed Set

Bad Boys of the Night: Eight Sizzling Paranormal Romances: Paranormal Romance Boxed Set From Jennifer Ashley, With Love: Three Paranormal Romances from Bestselling Series

From Jennifer Ashley, With Love: Three Paranormal Romances from Bestselling Series The Longest Night: Fantasy Romance (Nvengaria Book 4)

The Longest Night: Fantasy Romance (Nvengaria Book 4) The Many Sins of Lord Cameron hp-3

The Many Sins of Lord Cameron hp-3 Mate Claimed su-4

Mate Claimed su-4