- Home

- Jennifer Ashley

Death in Kew Gardens

Death in Kew Gardens Read online

Praise for the Below Stairs Mysteries

“A top-notch new series that deftly demonstrates Ashley’s mastery of historical mysteries by delivering an impeccably researched setting, a fascinating protagonist with an intriguing past, and lively writing seasoned with just the right measure of dry wit.”

—Booklist

“An exceptional series launch. . . . Readers will look forward to this fascinating lead’s future endeavors.”

—Publishers Weekly (starred review)

“A smart and suspenseful read, Death Below Stairs is a fun series launch that will leave you wanting more.”

—Bustle

“This mood piece by Ashley is not just a simple murder mystery. There is a sinister plot against the crown and the race is on to save the queen. The characters are a lively, diverse group, which bodes well for future Below Stairs Mysteries, and the thoroughly entertaining cast will keep readers interested until the next escapade. This first installment is a well-crafted Victorian adventure.”

—RT Book Reviews

“A fun, intriguing mystery with twists and turns makes for a promising new series.”

—Red Carpet Crash

“A charming new mystery series sure to please!”

—Fresh Fiction

“What a likable couple our sleuths Kat Holloway and Daniel McAdam make—after you’ve enjoyed Death Below Stairs, make room on your reading calendar for Scandal Above Stairs.”

—Criminal Element

Titles by Jennifer Ashley

Below Stairs Mysteries

A SOUPÇON OF POISON

(an ebook)

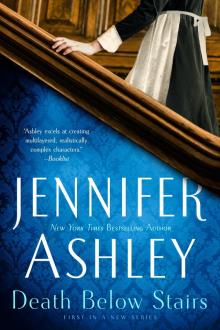

DEATH BELOW STAIRS

SCANDAL ABOVE STAIRS

DEATH IN KEW GARDENS

The Mackenzies Series

THE MADNESS OF LORD IAN MACKENZIE

LADY ISABELLA’S SCANDALOUS MARRIAGE

THE MANY SINS OF LORD CAMERON

THE DUKE’S PERFECT WIFE

A MACKENZIE FAMILY CHRISTMAS

THE SEDUCTION OF ELLIOT MCBRIDE

THE UNTAMED MACKENZIE

(an ebook)

THE WICKED DEEDS OF DANIEL MACKENZIE

SCANDAL AND THE DUCHESS

(an ebook)

RULES FOR A PROPER GOVERNESS

THE SCANDALOUS MACKENZIES

(anthology)

THE STOLEN MACKENZIE BRIDE

A MACKENZIE CLAN GATHERING

(an ebook)

BERKLEY PRIME CRIME

Published by Berkley

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

1745 Broadway, New York, NY 10019

Copyright © 2019 by Jennifer Ashley

Penguin Random House supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for every reader.

BERKLEY is a registered trademark and BERKLEY PRIME CRIME and the B colophon are trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Ashley, Jennifer, author.

Title: Death in Kew Gardens / Jennifer Ashley.

Description: First edition. | New York, NY : Berkley, 2019 | Series: A below stairs mystery ; 3

Identifiers: LCCN 2019001011 | ISBN 9780399587900 (paperback) | ISBN 9780399587917 (ebook)

Subjects: | BISAC: FICTION / Mystery & Detective / Women Sleuths. | FICTION / Mystery & Detective / Historical. | GSAFD: Mystery fiction.

Classification: LCC PS3601.S547 D45 2019 | DDC 813/.6—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019001011

First Edition: June 2019

Cover art by Larry Rostant

Cover design by Emily Osborne

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Version_1

Contents

Praise for the Below Stairs Mysteries

Titles by Jennifer Ashley

Title Page

Copyright

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

About the Author

1

September 1881

The Chinese gentleman ran from between the carriages that packed the length of Mount Street and straight into my path. I had no chance—he emerged so suddenly and without my seeing him that I barreled directly into the poor man.

My basketful of produce slammed into his narrow belly, knocking him from his feet. He landed on the cobblestones in a tangle of limbs and fabric.

I shoved my basket at my assistant, Tess, and bent over the unfortunate man.

“My dear sir, I do beg your pardon—you popped out so quickly.” I thrust my hands down to him, intending to help him to his feet.

Instead of accepting my assistance, the man cringed from me, his face screwing up in abject fear.

“Come now,” I said, softening my voice. “You can’t stay on the cobbles—they’re full of mud and muck.”

The man hesitated, still afraid, so I firmly took hold of him and hauled him to his feet.

He was small boned and light, easily lifted, but I felt strength under his garments. Once he was standing upright, I saw that he was a few inches taller than I, dressed in a silk robe that fell to his feet, the sleeves so wide his hands would disappear if he folded them together.

His round cap had fallen to the ground, revealing a head that was quite bald from forehead to the top of his skull. As though to make up for the lack of hair in front, a thick braid hung down his back to his knees, and a beard curled to his chest.

His robe was a deep blue, with birds and vines embroidered on the hem in rich yellow and green. The colors were muted from dust, rain, and London grime, but the garment must have once been lovely.

The Chinese gentleman finally lost his agitation and looked at me directly. He was not a young man, middle aged perhaps, though his hair and beard held little gray and his face bore only a few lines. But his eyes, which were dark brown, nearly black, contained a weight of years greater than my own, an understanding that comes from experiencing life, all its tragedies and triumphs. He had an air of supreme confidence that even falling to a London street could not erase.

This gentleman stared at me a moment longer before he tucked his hands into his sleeves, dropped his gaze, and gave me a slight bow. “Forgive me, madam.”<

br />

“Not at all,” I said briskly. “I knocked you over, sir, so I ought to apologize. Do take care as you walk about. The drivers do not go as cautiously as they should, and they can’t always stop their heavy drays in time. I would hate to think of you lying hurt on the street.”

He listened to my speech without blinking, though he transferred that keen gaze to my left shoulder. I sensed Tess behind me, gawping at the man with no sense of her own rudeness.

“Please accept my many apologies, good lady,” he said.

His manners were exquisite, such a refreshing change from those of men who had no intention of being courteous to a mere cook.

“No harm done,” I said. “Now, you must excuse me, sir. I need to walk past you, and there is very little room on the road today.”

The corners of the man’s eyes crinkled with good humor. As he bent to sweep up his cap, I saw razor scars on the top of his scalp from many years of shaving back his hair.

He gave me a final nod and darted off, moving swiftly between the carriages, around the corner to Park Street. I watched until he disappeared from sight then I took my basket from Tess, and we walked on.

“Well, that was interestin’,” she said in her cheery tones. “You don’t see many Chinamen in these parts. I’m surprised he’s allowed to walk in Mayfair.”

I shrugged. “He likely works for a family here, as we do.”

Even as I spoke, I felt a frisson of doubt. I’d been employed at the Rankin house on Mount Street long enough to have become acquainted with the servants in the homes around it, and none employed a Chinese gentleman.

Also, I did not believe he was a common laborer, as were many Cantonese who had come to London to escape poverty or war in their own country. While the gentleman had been afraid when I’d first knocked him down, he’d stood proudly on his feet, without the slumped shoulders of a menial. His faded robe had once been fine, the touch of the silk like gossamer.

“I’d never be Chinese,” Tess said, swinging her basket. “I hear their women stuff their feet into tiny little shoes.” She kicked out her long foot in its high laced boot. “Can’t work if you do that.”

“You couldn’t help being Chinese if your parents were,” I pointed out. “And the women in China from our walk of life work just as hard as we do.”

“If you say so, Mrs. H.,” Tess said. She crowded close and tucked her hand under my arm. “We’re packed in tight today, ain’t we? Her ladyship next door has no business inviting so many to her house for an afternoon. She’s ruined the whole street.”

Lady Harkness, wife of a knight of the realm, was holding a gathering today to show off her husband’s exquisite and unusual garden, full of plants he’d brought home from his years in the Orient. As it was September, most families of note were off in the country, hunting foxes or shooting birds flushed out by their servants, but Lady Harkness still managed to fill her gathering. Her husband was decidedly middle class and possibly lower, said Mrs. Bywater, the mistress of my house, with a sniff. Sir Jacob had been given a knighthood for services to the Empire, but he’d been born a tradesman in Liverpool.

Regardless of his beginnings, his wealth had brought him much prestige. The number of fine carriages that lined Mount Street and wrapped around the corner showed that his humble beginnings had been forgiven.

Not only did the waiting carriages jam up the works, but carts, wagons, and foot traffic served to clog the area further. Even the most elegant corner of London was a thoroughfare to somewhere else.

Mrs. Bywater was attending the garden party, in spite of her snobbishness about Sir Jacob and his wife. So was her niece, Lady Cynthia, with whom I’d formed a friendship. Both ladies wanted a look at the strange plants Sir Jacob had brought back from his many years in foreign parts. Lady Cynthia would tell me later about Lady Harkness’s do, most likely how horrifically wearying it had been.

For now, I had to get supper on the table for the family when they returned and for the entire body of servants—a dozen of us—who kept the Mount Street house running efficiently.

I entered the kitchen, exchanging coat and hat for apron, and began to sort through the comestibles, my encounter with the Chinaman fading to the back of my mind.

While Lord Rankin, a baron, owned the house where I lived and worked, he allowed Lady Cynthia, sister of his deceased wife, and her aunt and uncle, the Bywaters, to occupy the house while he dwelled in Surrey. Cynthia’s aunt and uncle had moved in to chaperone her, and also to keep her behavior in check—at least Mrs. Bywater considered this to be part of her duty. She and her husband wished to get Cynthia married off, out of harm’s way, but Cynthia, so far, had resisted.

The family had remained in residence through the sticky, smelly, uncomfortable London summer. Mr. Bywater always had much business in the City, and Lady Cynthia refused to return to her father’s house. Therefore, my duties had not eased during the hot months, and the kitchen had become like the devil’s anteroom.

Tess and I and the rest of the staff had sweated and struggled, our tempers short. A walk outside had scarcely brought any relief, as the heat enveloped the entire city. At least we were mercifully away from the river and its stink.

September brought welcome coolness and abundance as farmers began to cart in the harvest. Potatoes and apples gradually dominated the vendors’ carts, as well as walnuts and game from the countryside—partridges to venison. Mr. Bywater did not hunt or shoot, but he had friends who sent him whole birds or meat packed in paper and sawdust. Such a savings, Mrs. Bywater never failed to state.

One lesson the penny-pinching Mrs. Bywater learned, however, through the long, roasting summer, was that we truly needed a housekeeper.

Mr. Davis, the butler, and I had taken on much of the housekeeping duties, but I was too busy cooking, Mr. Davis too busy tending to the wine, silver, and service at table, to take care of much else. Discipline deteriorated among the maids and footmen, and tasks did not get done. I insisted on a large share of the household budget for food, but Mr. Davis wanted it for the master’s wine and brandy. We quarreled frequently, and Mrs. Bywater lost her patience with us.

Mr. Davis told me, triumphantly, a week ago, that Mrs. Bywater had finally broken down and asked an agency to send her candidates for a housekeeper. She hadn’t found one she liked yet, but at least she’d begun the proceedings.

Until then, it fell to me to go over the household accounts, keep inventory of the food, supervise the kitchen staff, and cook until my hands were sore, burned, and abraded.

Tess had proved to be quite capable, learning what I taught her quickly, and was beginning to master recipes and more complicated cooking techniques. She’d been scrubbing floors before I’d taken her on—a sad waste of talent. She’d make a fine cook after more training.

I did not muse on my encounter with the Chinese gentleman the rest of that day, as I had much to do. The next day was also particularly busy, and by the time I prepared the evening meal, I was short-tempered and exhausted. Mr. Davis blamed me for a missing bottle of wine—had I put it into my sauce by mistake?

When Charlie, the kitchen boy, spotted the wine behind a stack of greens, had Mr. Davis apologized and owned he’d been wrong? No, he’d sniffed, tucked the bottle under his arm, given Charlie a half-hearted clout on the ear, and stalked away.

I could only shake my head and return to my sauté pan, hoping I hadn’t ruined my sole in butter sauce. The butter had to brown, not burn, or the entire dish was spoiled.

Mr. Bywater liked his supper the moment he returned home, and we were a bit behind with the soup and greens. I thickened the soup with flour instead of letting it reduce, tossed in some cream and a good handful of salt, and sent it up.

Then Emma, the downstairs maid, spilled half my perfected butter sauce on the floor, and fell to weeping. I plunked the rest of the meal onto platters to go up in the dumbwaiter, told Te

ss to see to the staff’s supper, caught up a basket, and went out through the scullery.

Cool air touched my face as I walked up the stairs to the night, and I breathed a sigh of relief. I usually did not mind my life as a cook, but at times I found it trying. I reminded myself of the virtue of hard work and the fact that I was saving my shillings for the day I could reside with my daughter and run a little tea shop, the two of us living in bliss. Sometimes this vision helped, but tonight, peace eluded me.

In spite of my pique, I hadn’t forgotten those in more need than myself. My basket held scraps I’d saved from the meal—greens too wilted for the dining room, trimmings of cooked meat or fish sliced off for symmetry, fruit too squashed to look fine in the bowl, and dried ends of yesterday’s cake.

The few who gathered outside, knowing I would appear with my basket, swarmed to me with gratefulness. I handed out the food in pieces of towel that would have only gone into the rag bag.

A slim figure joined those in the shadows. I always met the beggars exactly between the streetlamps, where the darkness was greatest. The poor things feared the light, knowing they could be arrested for being unemployed and hungry.

I turned to the newcomer with my last bundle of scraps. “Now, sir, get that inside you, and you’ll feel better . . . Oh.”

I was surprised to see my Chinese gentleman from the day before. His long beard was a wisp against his robes, the blue of the silk black in the shadows.

He held out a box to me, a small wooden casket. “Please,” he said. “A gift for you.”

I held up my hands. “No, no, you do not need to give me anything.”

“You did me a kindness, madam. Allow me to thank you by doing one for you.”

“You are courteous,” I said, softening. “And I thank you, but I cannot possibly accept it. A gentleman does not give gifts to a lady, especially one he is not acquainted with. I am not certain of your customs in China, but in England, I am afraid that is the case.”

His eyes glinted as he raised his head, and I saw in them a flash of hurt. I felt contrite—I must have insulted him.

Grant

Grant Pride Mates

Pride Mates The Duke's Perfect Wife

The Duke's Perfect Wife Scandal Above Stairs

Scandal Above Stairs White Tiger

White Tiger Midnight Wolf

Midnight Wolf Rules for a Proper Governess

Rules for a Proper Governess Wild Wolf

Wild Wolf Bad Wolf

Bad Wolf Lion Eyes

Lion Eyes Murder in Grosvenor Square

Murder in Grosvenor Square The Untamed MacKenzie

The Untamed MacKenzie Wicked Deeds of Daniel Mackenzie

Wicked Deeds of Daniel Mackenzie Tiger Striped_Shifters Unbound

Tiger Striped_Shifters Unbound Murder Most Historical

Murder Most Historical Shifter Made

Shifter Made Mate Bond

Mate Bond Tiger Striped

Tiger Striped Bodyguard

Bodyguard Guardian's Mate

Guardian's Mate From Jennifer Ashley, With Love

From Jennifer Ashley, With Love The Longest Night

The Longest Night The Stolen Mackenzie Bride

The Stolen Mackenzie Bride The Sudbury School Murders

The Sudbury School Murders The Care & Feeding of Pirates

The Care & Feeding of Pirates The Hanover Square Affair

The Hanover Square Affair Death Below Stairs

Death Below Stairs Wild Things

Wild Things Wild Cat

Wild Cat The Gentleman's Walking Stick

The Gentleman's Walking Stick A Regimental Murder

A Regimental Murder Lone Wolf

Lone Wolf Forbidden Taste

Forbidden Taste Red Wolf

Red Wolf The Madness of Lord Ian Mackenzie

The Madness of Lord Ian Mackenzie A Covent Garden Mystery

A Covent Garden Mystery The Pirate Next Door

The Pirate Next Door Past Crimes: A Compendium of Historical Mysteries

Past Crimes: A Compendium of Historical Mysteries Highlander Ever After

Highlander Ever After The Alexandria Affair

The Alexandria Affair A Shifter Christmas Carol

A Shifter Christmas Carol The Devilish Lord Will

The Devilish Lord Will Adam

Adam Kyle (Riding Hard Book 6)

Kyle (Riding Hard Book 6) A Body in Berkeley Square

A Body in Berkeley Square The Mad, Bad Duke

The Mad, Bad Duke Mate Claimed

Mate Claimed A Mackenzie Clan Christmas

A Mackenzie Clan Christmas The Seduction of Elliot McBride

The Seduction of Elliot McBride The Glass House

The Glass House Iron Master (Shifters Unbound Book 12)

Iron Master (Shifters Unbound Book 12) A Mackenzie Family Christmas: The Perfect Gift

A Mackenzie Family Christmas: The Perfect Gift Scandal Above Stairs_A Below Stairs Mystery

Scandal Above Stairs_A Below Stairs Mystery Perfect Mate

Perfect Mate Murder in the East End

Murder in the East End Snowbound in Starlight Bend

Snowbound in Starlight Bend Hard Mated

Hard Mated Murder in St. Giles

Murder in St. Giles Alec Mackenzie's Art of Seduction

Alec Mackenzie's Art of Seduction A MacKenzie Clan Gathering

A MacKenzie Clan Gathering Tyler

Tyler Lady Isabella's Scandalous Marriage

Lady Isabella's Scandalous Marriage Duke in Search of a Duchess: Sweet Regency Romance

Duke in Search of a Duchess: Sweet Regency Romance A Death in Norfolk

A Death in Norfolk Give Me One Night (McLaughlin Brothers Book 4)

Give Me One Night (McLaughlin Brothers Book 4) Iron Master

Iron Master The Many Sins of Lord Cameron

The Many Sins of Lord Cameron A Disappearance in Drury Lane

A Disappearance in Drury Lane Never Say Never (McLaughlin Brothers Book 3)

Never Say Never (McLaughlin Brothers Book 3) Death in Kew Gardens

Death in Kew Gardens Ross: Riding Hard, Book 5

Ross: Riding Hard, Book 5 Ray: Riding Hard

Ray: Riding Hard A Soupçon of Poison

A Soupçon of Poison Tiger Magic

Tiger Magic The Pirate Hunter's Lady

The Pirate Hunter's Lady A Mystery at Carlton House

A Mystery at Carlton House The Necklace Affair

The Necklace Affair Wolf Hunt

Wolf Hunt Scandal and the Duchess

Scandal and the Duchess Kyle

Kyle Why Don't You Stay? ... Forever (McLaughlin Brothers Book 2)

Why Don't You Stay? ... Forever (McLaughlin Brothers Book 2) Bear Attraction

Bear Attraction The Gathering

The Gathering A Mackenzie Yuletide

A Mackenzie Yuletide Wild Things (Shifters Unbound #7.75)

Wild Things (Shifters Unbound #7.75) The Redeeming

The Redeeming The Seduction of Elliot McBride hp-5

The Seduction of Elliot McBride hp-5 Death at the Crystal Palace

Death at the Crystal Palace Mackenzie Family Christmas: The Perfect Gift (highland pleasures)

Mackenzie Family Christmas: The Perfect Gift (highland pleasures) Forbidden Taste: A Vampire Romance (Immortals)

Forbidden Taste: A Vampire Romance (Immortals) Care and Feeding of Pirates

Care and Feeding of Pirates Shifter Made (shifters unbound)

Shifter Made (shifters unbound) Dark and Dangerous: Six-in-One Hot Paranormal Romances

Dark and Dangerous: Six-in-One Hot Paranormal Romances The Duke’s Perfect Wife hp-4

The Duke’s Perfect Wife hp-4 The Seduction of Elliot McBride (Mackenzies Series)

The Seduction of Elliot McBride (Mackenzies Series) Lady Isabella's Scandalous Marriage hp-2

Lady Isabella's Scandalous Marriage hp-2 BodyGuard (Butterscotch Martini Shots Book 2)

BodyGuard (Butterscotch Martini Shots Book 2) The Wicked Deeds of Daniel Mackenzie hp-6

The Wicked Deeds of Daniel Mackenzie hp-6 Tiger Magic su-5

Tiger Magic su-5 The Madness Of Lord Ian Mackenzie hp-1

The Madness Of Lord Ian Mackenzie hp-1 Alec Mackenzie's Art of Seduction: Mackenzies (Mackenzies Series Book 9)

Alec Mackenzie's Art of Seduction: Mackenzies (Mackenzies Series Book 9) Mackenzie Family Christmas: The Perfect Gift

Mackenzie Family Christmas: The Perfect Gift Bodyguard (Shifters Unbound #2.5)

Bodyguard (Shifters Unbound #2.5) Midnight Wolf (A Shifters Unbound Novel)

Midnight Wolf (A Shifters Unbound Novel) White Tiger (A Shifter's Unbound Novel)

White Tiger (A Shifter's Unbound Novel) Cowboys Last All Night

Cowboys Last All Night Pride Mates su-1

Pride Mates su-1 Hard Mated (shifters unbound )

Hard Mated (shifters unbound ) Bodyguard (shifters unbound )

Bodyguard (shifters unbound ) Snowbound in Starlight Bend: A Riding Hard Novella

Snowbound in Starlight Bend: A Riding Hard Novella The Untamed Mackenzie (highland pleasures)

The Untamed Mackenzie (highland pleasures) The Untamed Mackenzie (Mackenzies Series)

The Untamed Mackenzie (Mackenzies Series)![Highland Pleasures [6] The Wicked Deeds of Daniel Mackenzie Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/07/highland_pleasures_6_the_wicked_deeds_of_daniel_mackenzie_preview.jpg) Highland Pleasures [6] The Wicked Deeds of Daniel Mackenzie

Highland Pleasures [6] The Wicked Deeds of Daniel Mackenzie Lone Wolf (shifters unbound)

Lone Wolf (shifters unbound)![Shifters Unbound [5] Tiger Magic Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/11/shifters_unbound_5_tiger_magic_preview.jpg) Shifters Unbound [5] Tiger Magic

Shifters Unbound [5] Tiger Magic Tyler (Riding Hard Book 4)

Tyler (Riding Hard Book 4) Ross

Ross Bad Boys of the Night: Eight Sizzling Paranormal Romances: Paranormal Romance Boxed Set

Bad Boys of the Night: Eight Sizzling Paranormal Romances: Paranormal Romance Boxed Set From Jennifer Ashley, With Love: Three Paranormal Romances from Bestselling Series

From Jennifer Ashley, With Love: Three Paranormal Romances from Bestselling Series The Longest Night: Fantasy Romance (Nvengaria Book 4)

The Longest Night: Fantasy Romance (Nvengaria Book 4) The Many Sins of Lord Cameron hp-3

The Many Sins of Lord Cameron hp-3 Mate Claimed su-4

Mate Claimed su-4